Our dogs and cats are an important part of our families and households but, depending on their lifestyle, they can encounter parasites that may pose a risk to either their health or to ours. It is important to understand the risks, monitor for infections and to help prevent disease in both our pets and our families, and to protect the environment in regard to the use of parasiticides (the medicines used to treat fleas, worms, ticks etc).

At Goddard Veterinary Group, we recommend twice-yearly preventative health checks, one with the Veterinary Surgeon at vaccination time, and one at a nurse check six months later. These appointments are the ideal time to discuss your pet’s lifestyle and their personal risk profile for picking up parasites. Preventing disease is better for your pet, your pocket and the environment than treating a disease once it is established.

Puppies and Kittens

Young animals have immature immune systems and are more at risk of life-threatening disease from parasites than adult cats and dogs. The veterinary surgeon will perform a full examination at the time of your first appointment and we ask you please bring a list of any treatments that your breeder or rescue centre may have given your puppy or kitten before rehoming.

Commonly seen parasites in puppies and kittens are:

- Roundworm – young animals are high risk of carrying roundworm which is a gastro-intestinal worm that can cause illness in young animals and blindness in people. Puppies can contract it in utero from their mother before birth. You may not always see evidence of roundworm, but occasionally they may pass in your pet’s faeces or be seen in vomit and look a bit like spaghetti.

- Fleas. These are often carried from their mother and can cause significant anaemia (red blood cell deficiency) in young animals. See below for how to detect fleas on your pet.

- Ear Mites. These are not uncommon in young animals and can cause a lot of irritation around the head. Our vet will examine the ears at their initial check-ups to check for signs.

Dogs and Lungworm

Lungworm is a serious illness that can be fatal to your dog if it goes undetected and untreated. 75% of foxes in London are believed to carry lungworm and it passes through slugs and snails and into your dog as larvae. Slugs and snails can be picked up when your dog chews grass and possibly from drinking from puddles or from dog bowls where slugs have been.

We recommend regular monthly prevention for but all but the most house-bound dogs in London. Preventative treatments are only available through a veterinary prescription and are not available in products sold over the counter or online without a prescription. We can offer prescriptions for either a Spot-On treatment or a chewable tablet.

If you dog is not on regular prevention, we will recommend a lung worm test prior to any surgery or if you dog is showing signs of being unwell.

Fleas – a problem for your pets, for you and your house

Fleas are probably the most common parasite we see and can cause immense irritation to you and your pet. They can also spread disease to people such as Cat Scratch Fever if we are bitten by them, and your pet can develop Flea Allergic Dermatitis. The risk of fleas increases in multi-pet houses, for pets that go outdoors and those that socialise with other pets.

The big issue with fleas, is that only the adult fleas live on your pet, and they account for only 5% of the flea population. The flea eggs, larvae and pupae live in the environment – they like a warm climate and fed off the dander (flakes of skin shed in your pet’s hair or fur). The pupae can hibernate for months and hatch as the adult flea when they feel warmth and vibrations of a mammal. The greatest risk of picking up fleas is over the spring and summer months, and then again when we turn on our central heating. Once a flea population is established in your house, it can take months to treat.

How to detect if you pet has fleas:

- Purchase a flea comb from your vet or a pet shop.

- Run the comb through your pet’s coat along the back, especially over the top of the tail.

- Shake any contents of the comb onto a wet tissue or paper towel.

- If you see black spots that turn red with blood, that is flea dirt.

We have a range of preventative treatments including ‘Spot-Ons’ and tablets and our veterinary team will make a recommendation to you based on your pet’s lifestyle and risk factors. Once an infection is confirmed on your pet, we will also recommend you treat your house, furniture, car, garden sheds and anywhere you pet may have been indoors that could keep the flea lifecycle going

Ticks

Ticks are another blood sucking parasite that can be picked up when your pet goes for walks in grassy areas. They can cause irritation and also transmit disease to your pet. They are mostly seen where other host animals live, such as deer, sheep and cattle. Dogs and cats living near some of London’s parks or those that travel outside of London are most at risk.

Do not remove a tick by pulling on it. The head parts will remain and can transmit disease or cause irritation and do not use spirit on it. Use a tick hook to twist the tick off with head parts attached. Tick hooks come with instructions for use.

Prevention. We recommend regular prevention if your pet is at increased risk of ticks, but not all pets will need it. Tick treatments are often combined with some flea treatments so check with your veterinary team if your flea treatment also covers for ticks. Tick treatments are available as a Spot On or as a tablet.

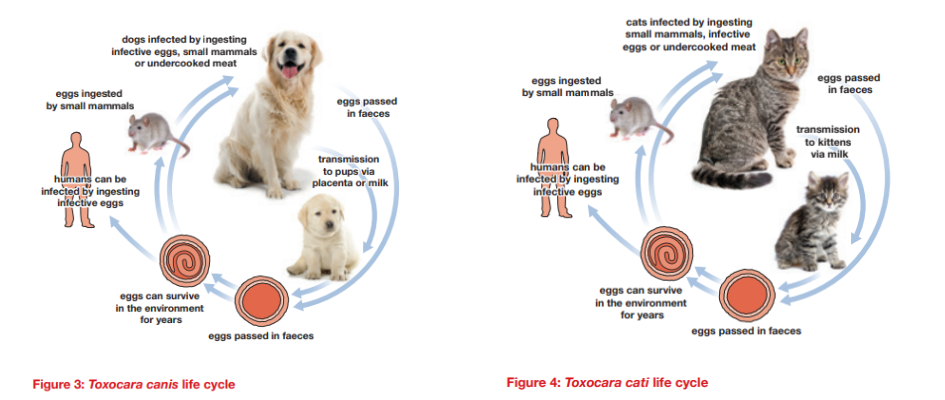

Roundworm – an intestinal worm in dogs and cats

As for puppies and kittens, adult cats and dogs are at risk of picking up roundworm. They live in the gastrointestinal tract, and you won’t often see visible signs. They can cause disease in people known as Toxocariasis and those most at risk are children and the immunosuppressed.

Eggs can be passed into the environment and survive a long time – that is why its important to pick up dog’s faeces and dispose of it in bins and not let pets play in sand pits or children’s playgrounds. Urban areas are reported to be at higher risk of roundworm than in country areas due to a higher density of pets and foxes. Your vet will recommend a regular worming program passed on your pet’s lifestyle. Cats that hunt, dogs that scavenge and feeding pets raw food will all increase the risk of roundworm.

See Feline Endoparasites: what is inside my cat and see Toxocarisis from the NHS for more on the risks to people.

Figure 1-Lifecycle images from ESSCAP Guideline 01 Sixth Edition May 2021

Tapeworm

There are a range of tapeworm species your pets can catch and three are a concern for human health:

Echnicoccus Granulosos in dogs: Can be picked up by eating raw offal and transmitted to people leading to large internal cysts known as hydatid cysts. Dogs that are scavengers, who travel to farming areas, or are fed raw food are at increased risk.

Echnicoccus Multilocluaris: Very common in Western Europe. Any dog that that travels to the EU must be treated before returning to the UK and we recommend treating again a month after returning.

Dipylidium caninum: If we accidentally ingest an adult flea this tapeworm can cause mild gastrointestinal symptoms.

Frequency of tapeworm treatment will be dependent on the lifestyle of your pet and whether they hunt, travel abroad, are feed raw food or live with immunosuppressed family members.

This covers the most commonly seen parasites in the Greater London area. However, there are a range of other creepy crawlies you and your pet may encounter and regular health checks are the best way to get an early diagnosis.

How to use parasite treatments safely:

All our parasite treatments will be dispensed with a data sheet that explains safe handling guidelines and we recommend reading these, especially if it is the first time you have used the treatment.

The British Veterinary Association advises the following to protect your pet, yourself and the environment from possible adverse effects of parasite treatment.

Keeping Pets Safe

- Only use products for the animal they’re prescribed for — they may harm others.

- Use the right product for the species — e.g. never use a dog product on a cat.

- Follow your vet’s advice on treatment frequency and when to finish the course.

- Avoid your pet’s eyes, ears and mouth when applying spot-on treatments and make sure other animals can’t groom or lick them.

Keeping People Safe

- Check the label to see if you are sensitive to any ingredients.

- Seek medical advice if you experience any adverse reactions.

- Avoid contact with your skin, eyes or mouth.

- Do no stroke or groom your pet until Spot-On treatments are dry.

Keeping the Environment Safe

- Discuss treatment options with your vet to minimise environmental risks.

- Check instructions before your pet is washed or swims. The medicine can wash off, stop working and harm wildlife and the environment.

- Dispose of the packaging safely and return unused products to your vet.

- Always pick up your pet’s poo and dispose of it responsibly.

Spot-Ons:

See our videos on our website at www.goddardvetgroup.co.uk for the most effective way to apply a Spot-On:

How to Apply a Spot On to a Dog

How to Apply a Spot On to a Cat

Always remember to follow the label and data sheet instructions on handling, swimming or bathing your pet after application.

Tablets:

Giving a tablet to your pet can be challenging but the parasiticide tablets we recommend are flavoured and chewable or can be wrapped in a treat to help with administration.

See our guide on ‘Giving your cat medication‘ for further information.

Don’t forget to bin and bag faeces when using an oral parasiticide tablet.